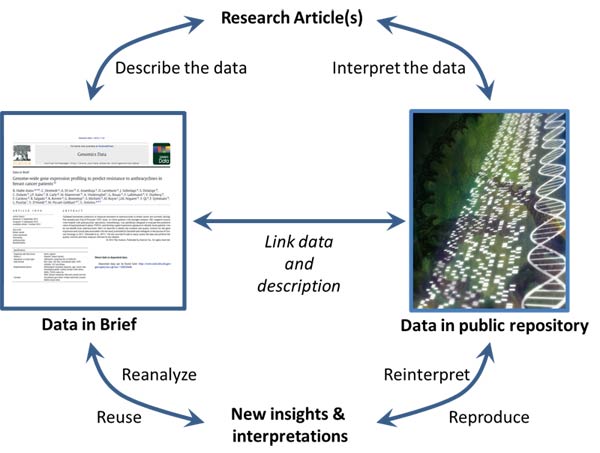

1) Be professional. It’s called peer review for a reason. You, putative reviewer, are the peer. If you don’t do it for them why should they do it for you? This is a core part of your job as an academic. It shows both that you are part of the academy and willing to engage in the interplay that makes the profession work. Reviewing is an excellent way to keep up with literature and a superb way to sharpen your own writing.

2) Be pleasant. If the paper is truly awful, suggest a reject but don’t engage in ad hominum remarks. Rejection should be a positive experience for all. Don’t say things in a peer review that you would not say to the person’s face in a presentation or in a bar after a conference.

3) Read the invite. When you receive an email inviting you to review a paper, most journals will provide a link to either accept and or reject. Don’t respond to the editor with a long apology about how you would love to do it but your cat has had kittens and you have a paper yourself to do, plus a class to teach.

4. Be helpful. Suggest to the authors how to overcome the shortcomings you identify. It’s the easiest thing in the world to poke holes in something. It is usually much harder to suggest how to fix them. A review is more than a suggestion to revise, reject or accept. It should be meaningful. It should guide the author on what is good and what is not so good as you see it. If it’s too short, then it probably isn’t going to do that. So be loquacious. Explain what is going on in your thinking. Suggest alternative approaches.

5) Be scientific. Your role is that of a scientific peer. It is not that of an editor in either the proofreading or decision-making sense. Don’t fall back on filling a review with editorial and typographic issues. If the paper is rife with errors, tell the editor and give examples. Concentrate rather on showing the added value of your scientific knowledge and not so much on missing commas etc. If as part of your revision you think that the paper should be professionally proof edited (as I sometimes do with my own), then say so. A caveat to this is that the paper (and indeed the review) is an act of communication. If it is so poorly constructed as to fail in its communication role, then tell me that. Remember that in the end the paper is not about style but substance, unless the style gets in the way.

6) Be timely. There is no point complaining about how slow the paper publication process is if you’re part of the problem. When you agree to review a paper with a timeline given (unless there is a really good reason), you should stick to it. Believe it or not, editors do track who is reviewing what and when. We have to balance the natural tendency to give more reviews to those who do most, with a realisation that people are doing this essentially pro bono and have limited time. So the timeframe we give is designed to be timely but mildly pressurising. Deadlines are good. Stick to them.

7) Be realistic. Be realistic about the work presented, changes you suggest and your role. You as a reviewer are part of the process. You don’t have final say on the determination of the manuscript. I, as editor, have that. Sometimes editors override the suggestions of reviewers (hopefully with good reasons). You can, and in that case engage, in a dialog with the editor as to why – ideally this is a learning opportunity for all. Sometimes this overriding is because the bar being set by the reviewer is too high for that paper. Data may not be available, a paradigm suggested not appropriate. These may be useful suggestions for another paper but each paper is, or should be, one main idea.

8) Be empathetic. Think of the best review you have gotten in terms of guiding a paper forward. Then think of the worst. Which would you rather get on average? Then put yourself into the shoes of the author whose paper you are reviewing. Where along the scale will your review fall? What goes around comes around and therefore ensuring that your reviews are scientific, helpful and courteous is a good idea.

9) Be open. Unless it’s a review for the Journal of Incredible Specialization, specialists and generalists both have a role to play. Editors, especially of general interest journals, will try to get both specialized and more general reviewers. Saying “it’s not my area” is rarely an excuse, especially when you have recently published a very closely related paper. Saying “I’m only one of the authors” in response, doesn’t cut it either. Editors try to balance reviews. That is why we ask for a number of reviewers. We may want a generalist, a subject specialist, someone with experience in the methodology and someone whose work is being critiqued. If we ask you then assume you have a valid and useful role to play.

10) Be organised. A review is, like a paper, a communication. It therefore requires structure and a logical flow. It is not possible to critique a paper for logical holes, grammatical howlers, poor structure etc if your critique is itself rife with these flaws. Draft the review as you go along, then redraft. Most publishers provide short guides on structuring a peer review on their website. Read some of these and follow the main principles. At the start, give a brief one or two sentence overview of your review. Then give feedback on the following: paper structure, the quality of data sources and methods of investigation used, specific issues on the methods and methodologies used (yes, there is a difference), logical flow of argument (or lack thereof), and validity of conclusions drawn. Then comment on style, voice and lexical concerns and choices, giving suggestions on how to improve.