History of traditional (closed) peer review

Even though scientific publishing has been around since the 17th century, formal peer review of submitted articles by external academics is relatively new. The journals Science and JAMA, for example, introduced formal peer review in the 1940s, and Nature didn’t introduce it until 1967.

The peer review system adopted in the 20th century has now become the norm for many journals. It involves an editor (usually a practicing researcher, but sometimes a journal staff member in the case of journals like Nature) sending out a paper to a few experts in the field, who then provide comments for the paper’s authors. Although the reviewers can generally see who the authors are, they themselves remain anonymous to the author, and only the editor knows everyone’s identity.

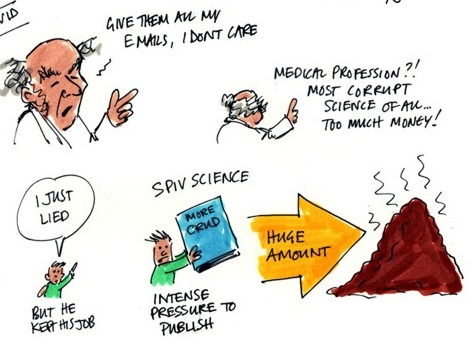

Problems with traditional, semi-blind, peer review

This “single-blind” system is not without problems. Anonymous reviewers can be biased against the authors of the paper, and lean toward rejection or acceptance for unscientific reasons. Often, the closest “peers” in someone’s area of research are also that researcher’s direct competitors! One solution is to remove the authors’ names from the manuscript, but this double-blind system is not fool-proof, and a reviewer will still often recognize which lab a paper comes from. In addition, any bias towards competitors of the reviewer still remain, even if that competitor is anonymized.

Another drawback of traditional peer review is that the referee reports are visible only to the authors and the editor. Nobody else can see what the reviewers thought of the paper. Especially in situations where reviewers disagree, and a single editor makes the final decision, it can be very informative to see what the reviewers thought of an article, and whether the editor’s decision was in line with their opinion. Reviewers are usually in a position to put the work in a broader context of the field, and often mention this context in their reports. They can also point out where the work could be expanded into new areas, and may still have some lingering questions. All of this is useful for everyone to read – not just the authors. It’s also important to remember that not all journals use the same criteria for publication. Some journals may turn a great paper down just because it doesn’t fit the scope of the journal. Other journals publish all sound science, including some papers that get extremely high praise in the referee reports.

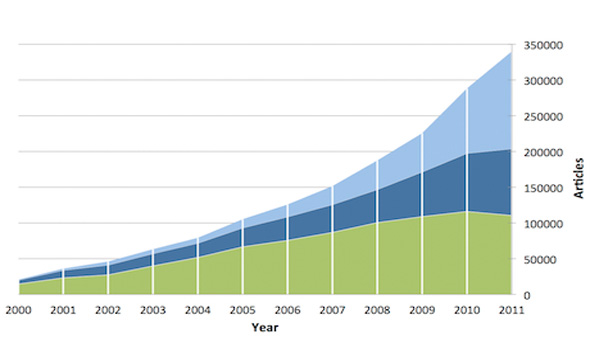

A timeline of open and transparent review

Within the life sciences in particular, several journals have opened their peer review process to address some of the issues discussed above. Sometimes this involves publicly naming reviewers and/or editors. Other journals publish some or all reviewer comments.

| 1999 | After studying various peer review models, BMJ starts revealing reviewer names to authors |

| 2000 | BioMed Central launches, and soon after that starts including reviewer names and pre-publication history for published articles in all medical journals in their BMC series of publications |

| 2001 | Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics introduces a system where manuscripts are placed online as a “discussion paper”, which is archived with all comments and reviews, even before approved and peer-reviewed articles appear in the journal. |

| 2006 | Launch of Biology Direct, which includes reviewer comments and names with published articles. |

| 2007 | Frontiers launches, and includes reviewer names with articles. |

| 2010 | EMBO journal starts publishing review process file with articles. Editors are named, but referees remain anonymous. |

| 2011 | BMJ Open launches, and includes all reviewer names and review reports with published articles. |

| 2012 | Several journals launch with an open peer review model:

|

Benefits of open review

Benefits for authors and readers

- Author can see who reviewed their work

- Reviewer comments put paper in context which is useful additional information for readers

- Reduces bias among reviewers

- More constructive reviews

- Published reports can serve as peer review examples for young researchers.

Benefits for reviewers

- Shows the reviewer’s informed opinion of the work

- Demonstrates experience as a reviewer

- Can take credit for the work involved in conducting the review

Challenges

Although open peer review is becoming more common, and addresses several of the issues of anonymous review, a few challenges still remain. A study in the early days of open review suggested that naming referees slightly reduced the likelihood of finding reviewers but did not affect the quality of review. Conversely, other studies suggest that open review provides more constructive reports.