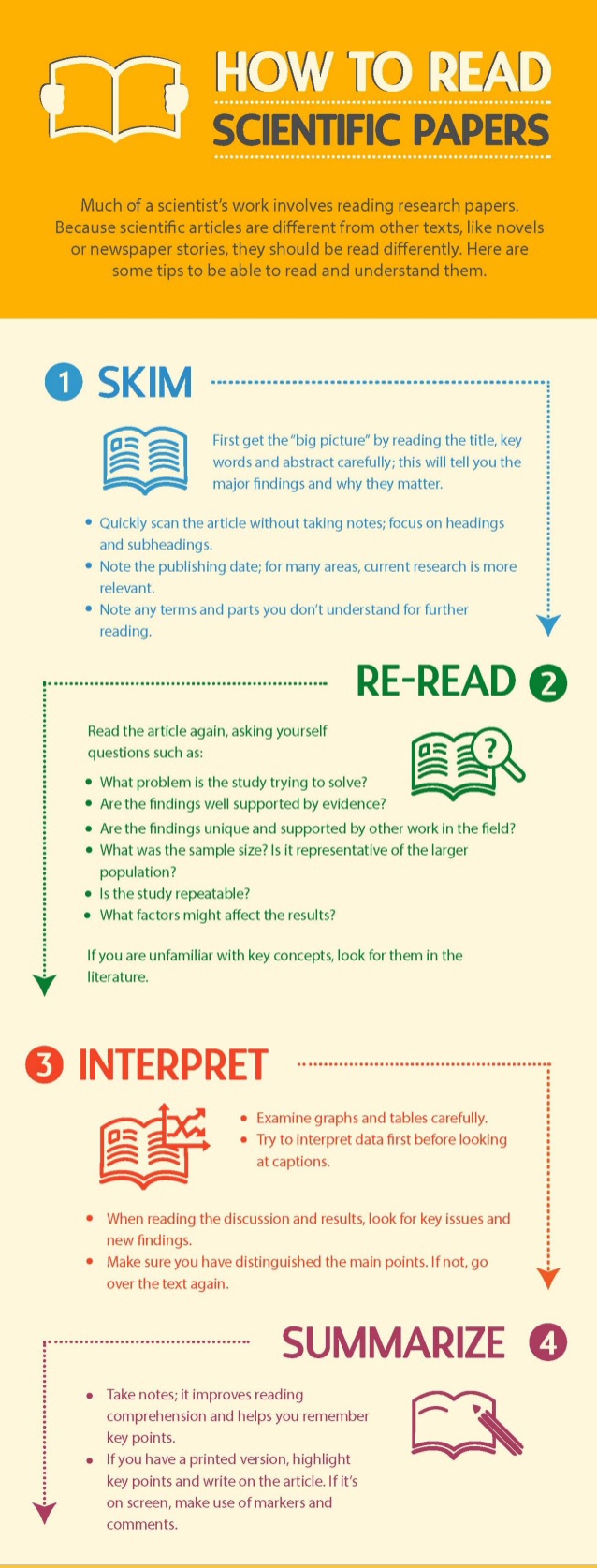

When an author decides to submit a manuscript for publication, that manuscript begins its life cycle, going through many phases as it is checked, refined and adjusted. Here we follow an article through its life cycle, to understand the different steps of the publication process and see how they contribute to ensuring an article is scientifically rigorous and accurately presented.

Phase 1: Conception and birth

The article is conceived in the author’s lab book, but it really comes to life once the author has written the manuscript. The fledgling article has been read by co-authors and supervisors, and it has been tweaked, checked and double-checked ready for submission.

The author has chosen a home for the article – the target journal – and checked the Guide for Authors to make sure the article is in the correct format. For many journals, Elsevier enables authors to submit in their chosen format through the Your Paper Your Way program, which means specific formatting isn’t needed until the article has been accepted. For most, though, requirements like line numbering and file format determine what the article looks like at submission.

Phase 2: Submission

The article leaves the author and begins its development in the journals submission system – home to more than a million articles a year. The article will soon be picked up and assessed by an editor and then the life cycle splits: the article may go back to the author, or move on to reviewers.

If the editor determines that the article is unsuitable for publication, the article will go back to the author with a rejection letter, suggestions for major changes, or an offer to submit to an alternative journal. The criteria depend on the journal, but scope and quality are two key requirements. If the journal is part of Article Transfer Service, the editor may suggest that the submission be transferred to another, more suitable journal. If the author chooses to transfer the submission, this submission phase of the life cycle will restart. If the editor thinks the article is suitable for the journal, and is of high enough quality, the article will move on to the next phase of its life cycle.

Phase 3: Reviewers

One of the pilots enables reviewers to discuss a paper with each other before they submit their reports. This helps reviewers align their feedback, making the decision of whether to publish easier for the editor. In another pilot, submitted abstracts are published before peer review and acceptance on the journal homepage of participating journals, such as Atmospheric Environment, profiling the authors and their work.

The peer review phase of the article’s life cycle is effectively the certification process, ensuring the article is suitable for the journal it’s heading for, and that it’s scientifically sound. In their review reports, reviewers make one of four recommendations to the editor:

- Accept without revisions (rare)

- Request minor revisions (such as adjusting tables and figures, rewriting sections)

- Request major revisions (could involve repeating experiments)

- Reject

Once the article has been assessed, it goes back to the authors to adjust, or submit to a different journal: the article either restarts the peer review phase, or returns to the submission phase. Assuming it continues on its cycle, the article is updated and is now in a state of near-completion. It has been checked, tweaked and checked, and is ready for publication.

Phase 4: Production and publication

The article has been accepted in its target journal, and it now enters the production phase, during which its appearance will change considerably. The editor’s job is complete, and the journal manager takes over the reins to guide the article through its transformation.

The first step is for the article to be converted into the journal’s specific layout. Typesetters transfer the text, tables, figures, links and references into the new layout, and stamp it with a CrossMark – an identification that shows readers whether they are looking at the most recent version of the article.

Next comes the proofing process: traditionally, this has been a source of delays in an article’s life cycle, so few journals are working on several projects to make the proofing process more efficient and easier for authors. Proof Central is a system that lets authors check their articles and correct mistakes directly in the text, instead of having to mark up a PDF. Automating the approvals process and enabling this direct interaction shortens this phase of the life cycle dramatically.

While the article is with the author for a final check, the journal manager assigns it to an issue of the journal and it’s uploaded to ScienceDirect. In its current format, the article is an accepted manuscript and it’s available in the articles in press section of the journal’s ScienceDirect site, complete with DOI. If the journal has an article-based publishing (ABP) process in place, the article is put directly into the next available issue in progress. This will be its home for the rest of its life. If the journal doesn’t yet use ABP, the article will wait in the articles in press area – a sort of waiting room – until it’s time to compile the issue.

The article has been checked by the author and it’s free of typos, full of interactive links and ready to enter the next phase. Our article is now in its permanent home online, fully citable, with a DOI and page numbers.

Phase 5: Dissemination and archiving

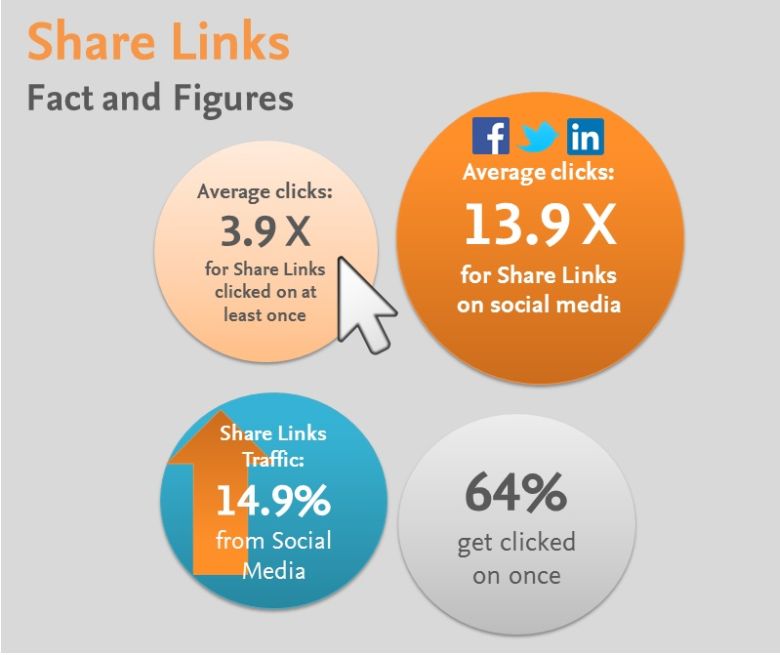

The article is published, but its life cycle isn’t yet complete. In this phase, dissemination can start; sharing the article helps increase readership and make it more visible. The author can share this link via email and on social media, and encourage colleagues, peers and other contacts to read the article. An earlier version of the article – the accepted manuscript – is also available on the author’s institutional website and on Mendeley. Through green open access, authors can share accepted manuscripts on academic sites for research and educational purposes.

The article is also archived at this stage. Occasionally, articles need to be corrected if a mistake slips through the proofing net during the production phase (we’re all human, after all). Since the article is archived and has a permanent home, any corrections that need to be made through corrigenda and errata, for example, can be linked to the article easily.

It’s also vital to make sure the article is available in perpetuity: archiving is very important for the scientific record. Archiving means that researchers can look back at the article for information long into the future; it’s still possible to find the original The Lancet paper describing Alzheimer’s disease from 1950.