Ten tips for reviewing

1. Ensure that the subject is within your purview of expertise: Thus, if you are an interventional cardiologist, it would probably be best if you declined an opportunity to review a manuscript involving the pathogenesis of an arrhythmia.

2. Read the abstract first to see if what the authors are stating makes logical sense and if it is written in a way that is comprehensible: Some manuscripts involve excellent work and interesting observations, but they are so poorly written that it is difficult to understand what the author is saying. This is a relatively common problem with authors whose native language is not English. If the work reported in the manuscript looks interesting and valuable, it should be sent back for editing by a native English speaker or professional translator.

3. Determine if the observation made and reported is something new or if it reproduces previously made observations? Clearly, the more original the observation, the more likely the manuscript should be accepted for publication.

4. Examine tables and figures to see if the legends are clear and if the tables and figures demonstrate the same thing that is stated in the text. Frequently, material placed in a table does not have to be reported in detail in the results section.

5. Look to see if the statistical analysis makes sense. Are the differences reported in the statistical analysis of sufficient magnitude to be of biological or clinical significance? Sometimes, a small statistically significant difference between two or more groups of patients is so small as to be “biologically insignificant.”

6. Examine the methods to make sure the authors knew what they were doing. If their laboratory analyses were just run on a commercial kit without input from someone in the hospital or medical school laboratory, these results may be of lower quality and higher variability. Make sure the study is based on a sufficient number of patients or measurements. Ask a biostatistician to review the manuscript if there is any question of the reliability of the analyses performed.

7. Read the discussion and see if it makes sense and if it reflects what the data in the article reports. Look for unnecessary conjecture or unfounded conclusions that are not based on the evidence presented.

8. Note whether the manuscript is concise and well organized. Most of the ones I receive could be shortened with improvement.

9. Note whether the quality of the figures or photos is adequate for accurate reproduction. If not, ask the journal staff (for example, the managing editor) what is required. Then, as part of your review, you can recommend that the authors have an expert at their institution reformat the figures to meet the specified requirements.

10. Please take this job seriously. It is a professional honor to be invited to review a scientific manuscript; the journal’s reputation depends in part on this peer review process.

5 reasons to pause

Stop and contact the journal’s editorial staff if you can answer “yes” to any of these questions:

1. Has the author neglected to follow the instructions that are part of your journal’s submission criteria?

2. Are there potential conflicts of interest either declared or not declared but known by the reviewer? If the review is not blinded, i.e., you know who the authors are, do they have a “track record” of working in this area, and are they from a reputable institution?

3. Was there appropriate informed consent (human experiments) with documentation that a human or animal protection committee reviewed the protocol prior to the initiation of the study?

4. Is the manuscript full of typographical errors or mistakes in references, implying a sloppy job of putting it together?

5. Is there a chance that there is scientific fraud or plagiarism involved in this manuscript? Subjectively, do you believe what the authors are telling you or do you suspect some consistent error in the hypothesis, methods, analysis of data, etc?

Ten things you need to know about the publishing process

1. Getting a paper published is a collaboration

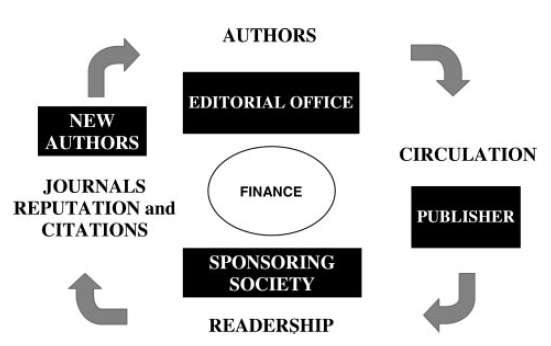

If there is one point that I’d most like you take away from this talk, it’s that the process of getting a paper published is a collaboration among authors, reviewers and editors. Authors are sending them the final product of their hard work. Editors are trying to select and improve upon the best of the papers that come to them. And reviewers are upholding the standards in the field and making valuable suggestions to improve the paper they are reviewing. Throughout my talk, I will point out how interactions between these three parties come into play.

2. Tell a story

Set up the question you are trying to address and tell why it’s interesting and important. Remember that your introduction is not an annual review article. Instead, focus on telling the reader the basics that they need to know so they can understand and appreciate the story you are about to tell. Remember that the chronology of the experiments is not important. Keep the logic of the experiments and the story front and center. Editors take great care to select the very best work for their journals. For this reason, they will often recruit papers in addition to the volume they receive every day to have as large a pool as possible from which to select. Therefore your paper has to stand out.

3. Sell your story

Your paper has to sell your work. Before submitting your paper, recruit colleagues outside of your area to review it, and ask for an honest appraisal. Is the flow of logic clear? Is all the jargon defined? Do the experiments support the conclusions? If English is your second language, ask a native English speaker to check for grammar and clarity of meaning. Pre-submission inquiries are a good idea if you want to gauge the level of enthusiasm for the work at different journals.

4. Avoid overloading

Authors try to impress editors and reviewers by packing the paper with all the experiments that were done in the main part of the paper as well as the supplementary information. Sometimes more is not better. In fact, with too many side stories, the major points can get lost. Again, think about the story you are trying to tell and whether the piece of data you are including is absolutely necessary to support that story. Sometimes reviewers will ask for additional experiments whether those experiments are necessary to make this story stronger or whether those experiments are best left for a follow-up paper.

5. Keep it simple

No reviewer has ever complained, “This paper was too simple to read,” but many have commented on how often papers are difficult to read. Authors worry that their paper will be seen as too simplistic if it is presented simply. Science is difficult enough – you don’t need the language to be complicated to make the research meaningful. Use words you would typically use when describing something. Avoid unnecessary jargon and buzzwords. Your paper needs to get past the editors to be sent out for review. If they can’t understand it, it won’t make the cut.

6. Don’t obsess about Impact Factor

Blockbuster papers may increase the Journal Impact Factor, but a growing number of methods are being used to measure the impact of research papers that take into account metrics such as downloads, views and share metrics.

7. Spend time crafting your cover letter

This is the attention getting “elevator pitch” that will help sell your research to the editor. Summarize how your work builds upon what’s been done before and how it advances work in the field. Be precise. Be honest. Let them know what the work does not do. Tell them about competition. Make reviewer suggestions and exclusions here. If your paper has been reviewed at another Cell Press journal, you can let them know so that we can use those reviewers’ comments. You can also decide to start the review process afresh.

8. What happens once your paper is received?

At Cell Reports every paper is read by one of their four science editors, who writes an assessment about whether it merits consideration for review. This assessment is then shared and discussed with the other scientific editors, and a consensus is reached about whether or not the paper is a strong candidate for formal review, or if a consult would be helpful. Cell Reports receives over 100 submissions per month. Since Cell Reports is so broad, they sometimes consult their editorial board, the in-house editors at other Cell Press journals, or other scientists about whether a paper is a strong candidate for Cell Reports. About half the papers received are sent out for review, and they typically publish about 25-30 papers a month.

9. Who are the reviewers, and what do they do?

Reviewers are researchers from academia and industry who have authored similar papers on related topics. Review periods are typically between 10 to 15 business days, during which the reviewers look carefully at each paper, commenting on the experimental design, how well the experiments support the conclusions, whether further experiments are needed, and the level of scientific advance the work represents. They ask reviewers to identify potential conflicts of interest before they receive the paper to review, based on the title and abstract.

10. What goes into the decision letter?

The editors spend time carefully reading the reviewers’ comments and deciding whether the authors should be invited to submit a revision or not. This is not a matter of simply counting up votes. Instead, they come back together as a group to discuss decisions. When the reviewers’ comments vary widely, they go back to the reviewers and ask them to assess each other’s comments anonymously to help them better gauge the level of importance of certain experiments or reservations they may have. Then they write a clear letter to the authors to explain which experiments or text changes need to be made in the revision. Alternatively, if the decision is negative, they hope that the reviewers’ comments prove useful to them in revising the paper for publication elsewhere. Even when the outcome is not positive, it is their hope that the author finds the process fast, fair and useful.

Posted in Impact Factor, Journal article, Journal Selection, Review article, Scientific editing, Scientific writing