Communication is a vital part of the academic process: sharing results with your peers means your research builds the knowledge base, adding to our understanding of the universe and everything that goes on inside it.

So why does the writing have to be so dull?

Research articles can be near enough impenetrable for most people, but even when readers do understand them, many are written in such a boring, unappealing way that they’re not exactly engaging page-turners. Does it matter?

For Dr. Filipe, Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Amsterdam, we could all stand to benefit from a big change in academic writing:

“As researchers, we like to think we’re creative, but in my opinion the scientific community is a very conservative place in reality. We repeat the same formulae over and over, including when we’re writing articles.”

It’s often journals themselves that set the formulae – some journals have such strict submission guidelines that authors are restricted at the sentence level. “Guidelines are important in a way, but when they’re so restrictive, you end up with an article with exactly the same structure as all the other articles in the journal,” Filipe says. “This affects me every day. I really enjoy reading scientific papers – I do it a lot – and maybe that’s why I’d like to see some novelty.”

Writing style is influenced by the greats

He has a theory of why scientific papers are slow to evolve:

“My hypothesis is that people often want to do things the way the greats do them – you can see this in music, for example, with people emulating their guitar heroes. Every once in a while there’s a revolutionary person, and all of a sudden everyone is following their new formula.”

It’s this top-down approach that holds back change in academic writing – originality is reserved only for people who are well established in their field, he says, with researchers telling themselves, “I’m not there yet, I don’t see myself as one of the greats. The way I tackle it is to stand by the style and language decisions I really believe in. Occasionally I try to stand a little more firm next to a paragraph a reviewer is criticizing for the way it’s written. I’m not talking about misstatements, or writing that’s unclear or ambiguous, but really about style choices.”

Influence is also powerful in terms of teaching the next generation of researchers. But is this a missed opportunity? “Most people I know who are great communicators tend to be great teachers who have engaging lectures,” Filipe says. “When you go to their lectures, you really enjoy them – they’re full of metaphors and they present the content in an interesting way. It’s a shame this very often doesn’t transpire in their writings.

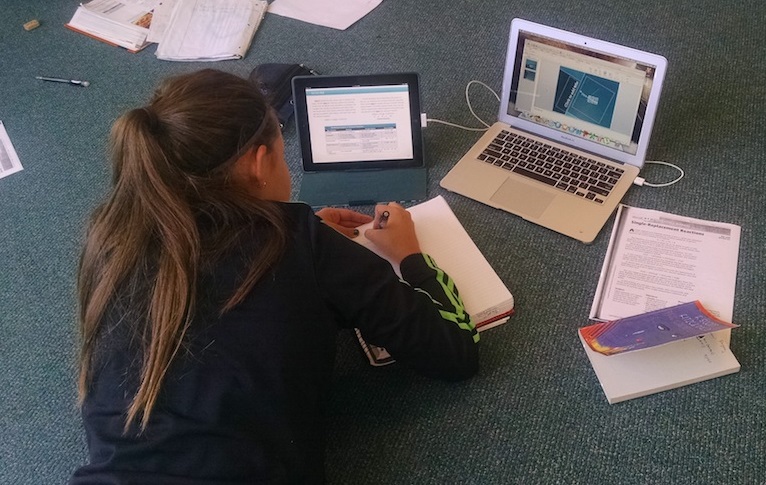

“I’m responsible for teaching a lot of future researchers how to write. It’s striking to me that we’re telling them how to make their writing clear and transparent, but in doing so, we’re actually making it very inaccessible because the way we have to write makes it incredibly tedious to read.”

Journals play a part in shaping style

Publishing also influences academic writing – reviewers and editors play important roles in this process. “The peer review process is a very important part of publishing,” he explains, “but it’s not just your science that’s on the line – reviewers often make stylistic judgments, and if your paper diverges too far from the norm it doesn’t fare well.”

The accepted approach to academic writing is formal and technical, and many editors and reviewers will suggest stylistic and language changes to an article. In doing so, though, they may be limiting the impact of a paper. “I think more engaging writing gets more people reading about your work – there are papers that have been cited more because of the way they were written,” he says.

“As a reviewer, I avoid stylistic comments – I tend to stick to the science, and I speak up when there’s something I don’t understand. What I care about is whether I get the message, and whether it’s logically sound. I’ll never make a comment about a word you have used unless I don’t agree with the idea I get from it; if I do, then it’s a problem of clarity.”

Improve by trying new things (that may not work out)

When authors – including less established ones – try something original in their writing, in the right situation, with the right journal it can be refreshing and engaging. But what if it’s not? According to Filipe, failure is OK, and it’s something we need to embrace if we’re going to make a change.

“Occasionally an author will try something new and it just won’t work. But that’s OK; the fact that they actually tried to do something different means something good can come out of it. Even if you’re simply showing how not to do it, you end up getting more exposure,” he says.

“Whether you like it or not, or think it’s appropriate or not, it’s a weird world where you don’t have the freedom to express your science the way you want to express it.”

So what’s the magic formula?

“Diversity is one of the things I’d like the most. I don’t only listen to jazz, or rock, or classical music, just as I don’t only like one style of article. Something I would never say is ‘this is the formula that everyone should be following.’ We need to get away from the idea that there is just one way of communicating a paper.”

5 ways to engage readers with your research

Try these simple tricks to freshen up your writing and entice more readers.

1. Give your article an interesting title. Make it clear to readers what your work is about, but keep the title short and snappy. The title is a great place to filter out unnecessary jargon. For example, the title “Analysis of the process of altering the flavor of the liquid beverage derived from plants of the family Rubiaceae using crystallized short-chain carbohydrates” might instead be “Analyzing the taste of coffee sweetened with sugar.”

2. Write in active sentences. Was the ball dropped by you, or did you drop the ball? Traditionally, academic writing is in the passive voice – grammatically, that means the subject of the sentence is the recipient of an action. But we engage more with stories about people; if you are the subject of a sentence, it becomes more naturally interesting. So instead of “the agar plates were incubated,” try “we incubated the agar plates.”

3. Write short sentences and paragraphs. One surefire way to lose readers is to write in long, complicated sentences. Academic subjects tend to bring with them a technical language with long words. Using technical terms already increases the difficulty of reading a piece of writing. If you want to keep hold of your readers and make sure they really understand your message, keep it short and sweet.

4. Don’t use unnecessary jargon. Sure, you’ll need to use some technical terms, but if you can make your writing more interesting with alternatives, give it a try. If you have a choice of words to use, and one is more recognizable than another, go with the familiar one. You could also introduce a technical term, then continue with the more familiar term, for example: “We tracked several colonies of Apis mellifera (honeybees) to see how far they travel to food. The honeybees flew up to …”

5. Enrich your article with Audio slides or a lay summary. editEon offers article enrichments so you can talk about your research in your own words or summarize your article for a wider audience.

Encrypting results for secrecy

In the 17th century, natural philosophers started to publish their discoveries, but competition to be first to make a discovery led many of them to develop a way of publishing without giving anything away. Newton, Hooke and Galileo were among those who started to publish anagrams. In his book Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science Michael Nielsen describes how Galileo first published his discovery of Saturn’s moons in an anagram:

“Instead of explaining forthrightly what he had seen, Galileo explained that he would describe his latest discovery in the form of an anagram: smaismrmilmepoetaleumibunenugttauiras. By sending this anagram, Galileo avoided revealing the details of his discovery, but at the same time ensured that if someone else – such as Kepler – later made the same discovery, Galileo could reveal the anagram and claim the credit.”

Being first isn’t such a powerful driver these days, but in a way, academic publishing does prevent many readers from understanding – or at least enjoying – research papers.

Leave a Reply